In the last decade, Pennsylvania’s Congressional districts have seen some rather dramatic changes. After the 2010 elections, Republicans secured both legislative and executive control in the state government, and they used it to draw aggressive gerrymanders for state legislative and Congressional maps. In the US House, this put Democrats at a disadvantage, as they could get about half of the statewide popular vote yet win only five seats, or 28%.

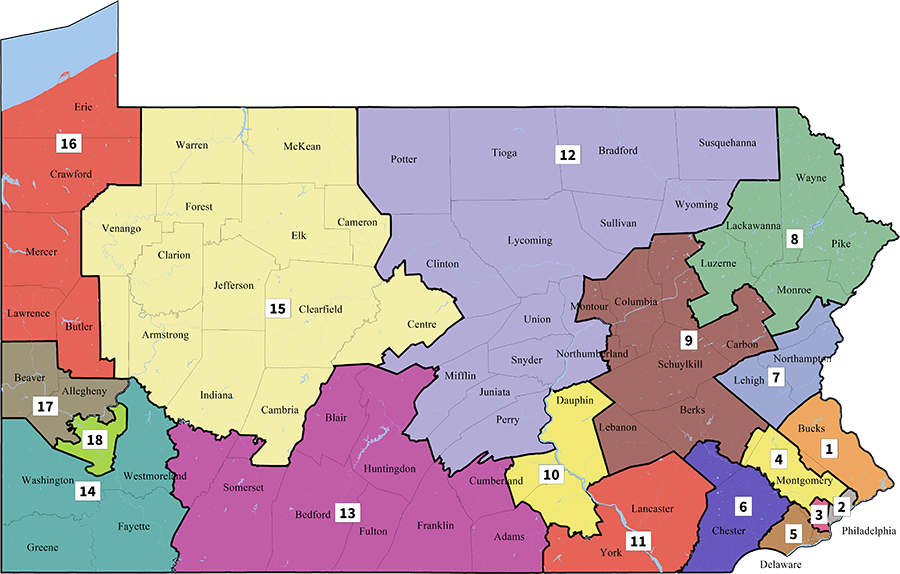

In 2018, League of Women Voters was able to successfully sue the state legislature at the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. In a 5-2 decision, the court struck down the Congressional map and asked the legislature to draw a new one. However, Republicans, who controlled the legislature, were unable to reach a deal with Governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat. The court ultimately resolved that it would draw the new map, by consulting Stanford law professor Nathaniel Persily. Mr. Persily produced a more compact map that gave greater attention to communities of interest.

It’s now 2021, and the US Census Bureau will soon release the PL 94-171 data set, which provides precise population and demographic data to draw districts. This task falls again to the state legislature in Pennsylvania, but maps must be approved by the governor. Given that control of the state government is still split, it is somewhat likely that redistricting will be handled by the state supreme court again.

Since the court has already commissioned a fair map, they may look to only make minor alterations to the existing districts, to preserve population equality. The map will also need to account for the elimination of Pennsylvania’s 18th Congressional District, which will be lost in reapportionment.

My proposal prioritizes these objectives, while also creating compact and competitive districts that keep communities of interest together.

The first six districts are in and around Philadelphia, and my new boundaries are fairly similar to the current ones, due to two factors: growth in population relative to the rest of the state, and the loss of one district. The former makes the districts shrink in size, and the latter makes them grow, resulting in a largely neutral effect.

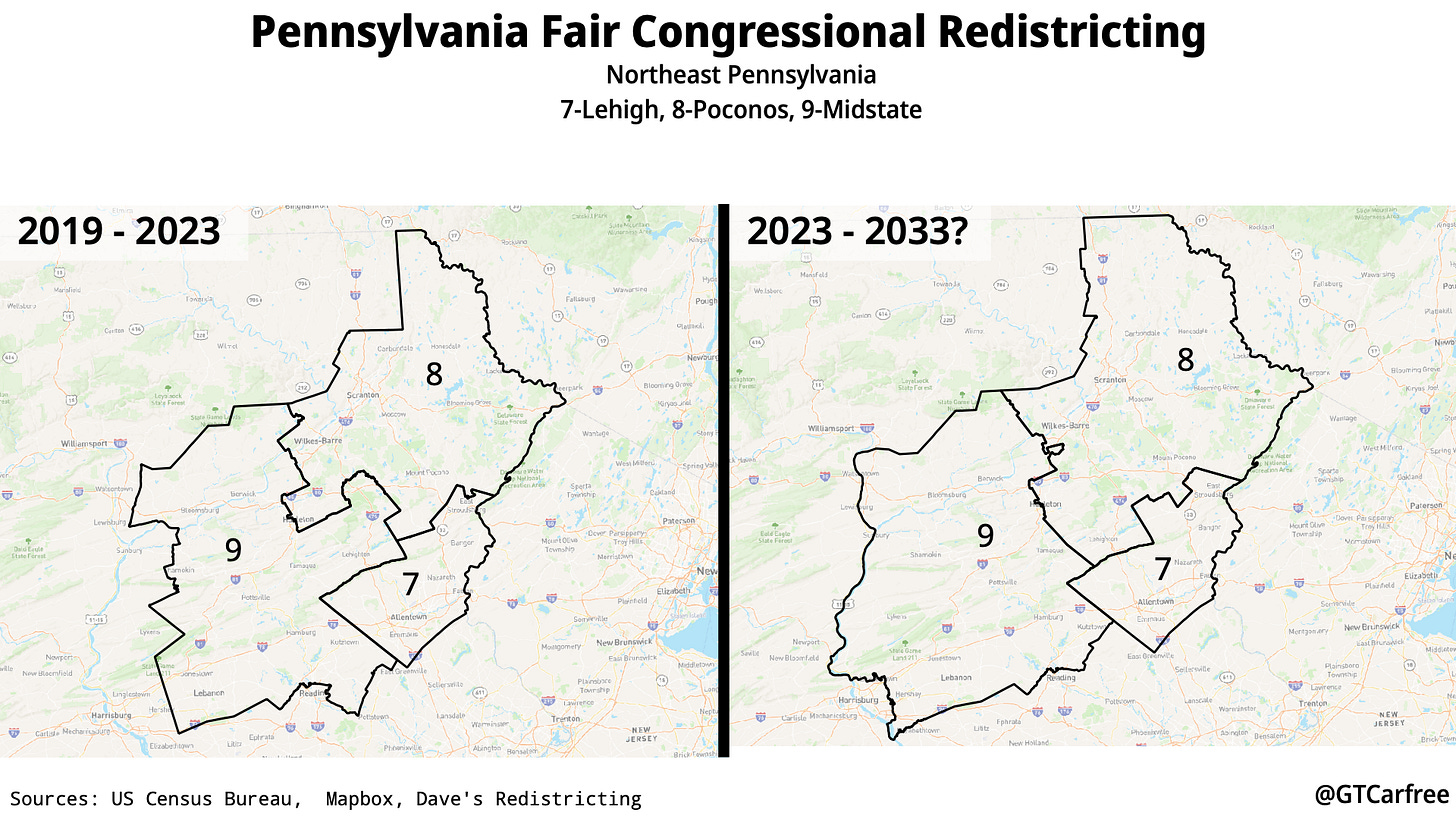

Core communities of interest are maintained in the northeast part of the state, with Allentown, Scranton, and Lebanon being kept in their current districts. The new boundaries also make the district shapes slightly more compact.

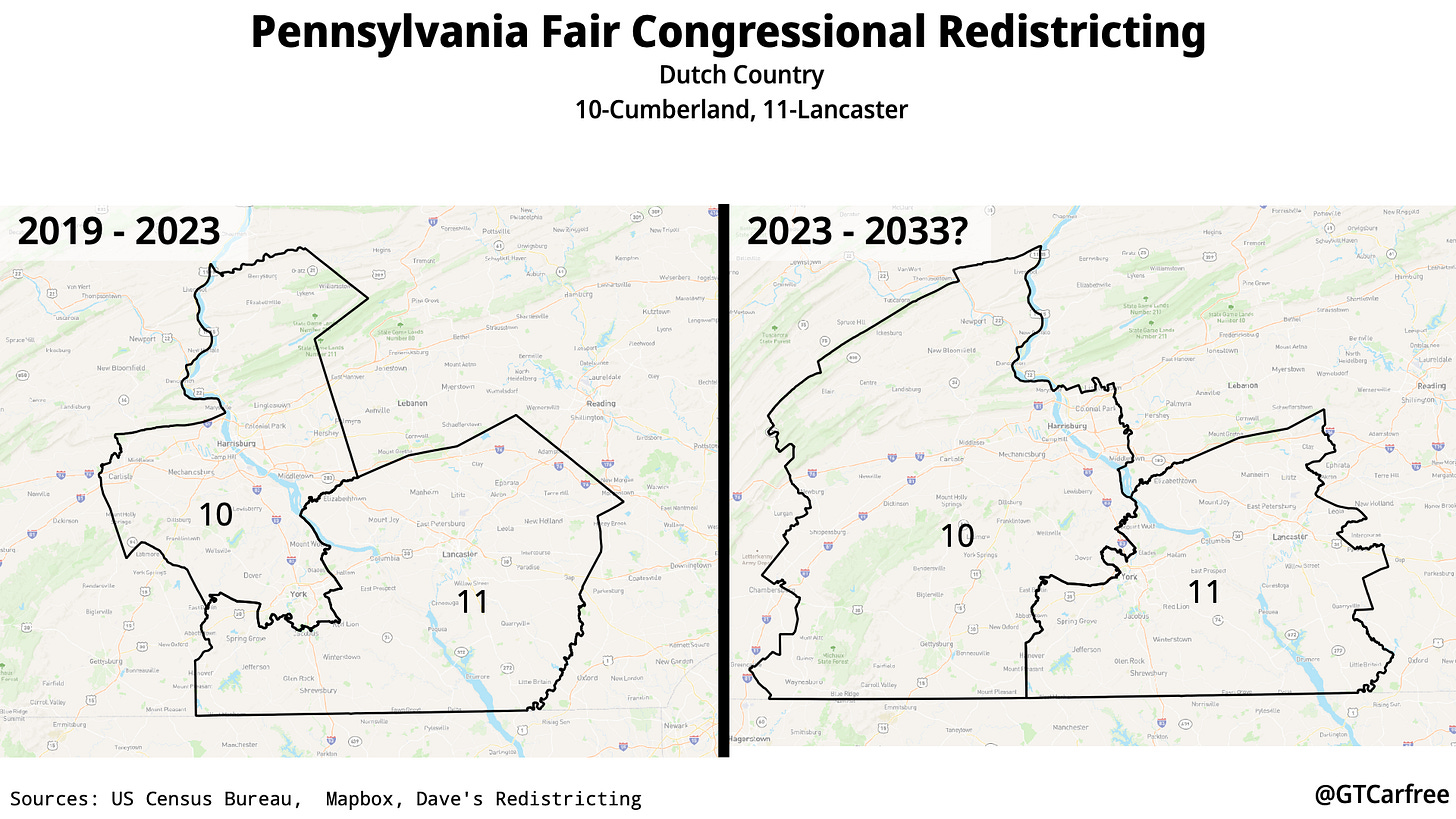

The two districts that occupy much of Pennsylvania’s Dutch Country (from the term Deitsch, or “German”) will be slightly altered, with the 10th District shifting south. It will consequently contain more of the Cumberland Valley. The 10th District will continue to have the state’s capital city, Harrisburg, and Lancaster County’s eponymous seat will remain in the 11th District.

Since Pennsylvania’s population loss is most concentrated in the rural part of the state, it makes the most sense to eliminate a district from that region. Here, the 16th District is combined with the 15th, with parts of the latter being given to the 12th and 13th.

Southwest Pennsylvania is centered around the state’s second-largest city, Pittsburgh. The 14th District now follows the Ohio River for parts of its northern boundary and reaches much closer to the Pittsburgh metro. The 17th and 16th Districts are the successors to the former 17th and 18th Districts, respectively. The city and metropolitan area is divided between the two districts, allowing for greater compactness and competitiveness.

In the aftermath of Common Cause v. Rucho, protections against partisan gerrymandering have only been enforced at the state level. While judicial intervention can shield against the most egregious cases, it will be optimal for Pennsylvania lawmakers to develop a well-organized commission to draw maps that respect redistricting principles.