Congressional Redistricting in Virginia (2023-2033)

Old redistricting practices are a thing of the past in the Old Dominion

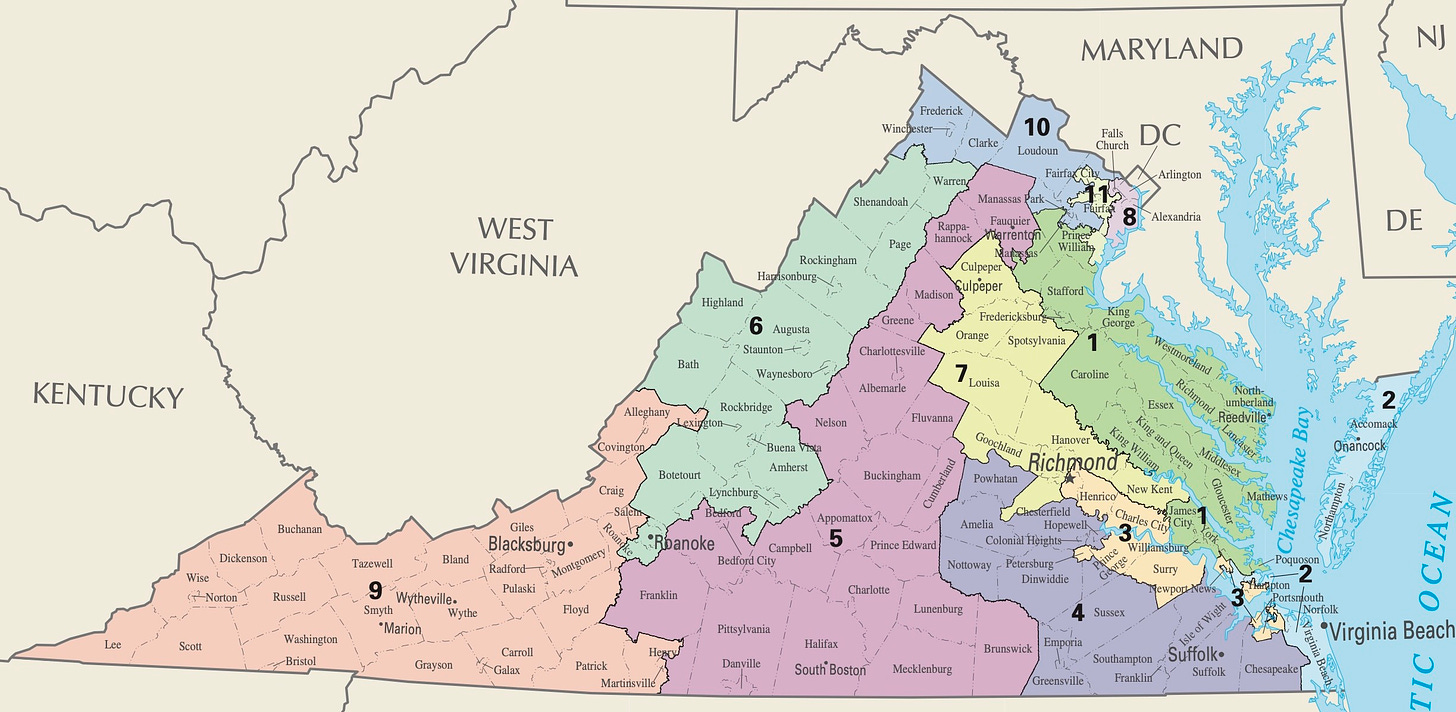

The 2011 Virginia state elections gave Republicans control of the General Assembly, and after taking the governorship in 2009, they were in a position to unilaterally draw Congressional maps for the next decade. Their gerrymander focused on locking in the 8-3 partisan split they gained after the 2010 US House elections. It packed Democratic voters into two districts in northern Virginia and one district stretching from Richmond down the James River. This allowed Democratic strength to be diluted elsewhere.

In 2014, Democrats sued the state in federal court, arguing that the Third District, represented by Bobby Scott, had been drawn in a manner to pack too many black voters in the region into one district. They contended that this arrangement would preclude black voters from having more proportionate political power by severely diluting their strength in surrounding districts. A panel from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia agreed and gave the General Assembly until early 2015 to pass a new map. However, by that point, Virginia had elected a Democratic governor, Terry McAuliffe. To break the deadlock, a panel from the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit appointed Dr. Bernard Grofman, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, as special master.

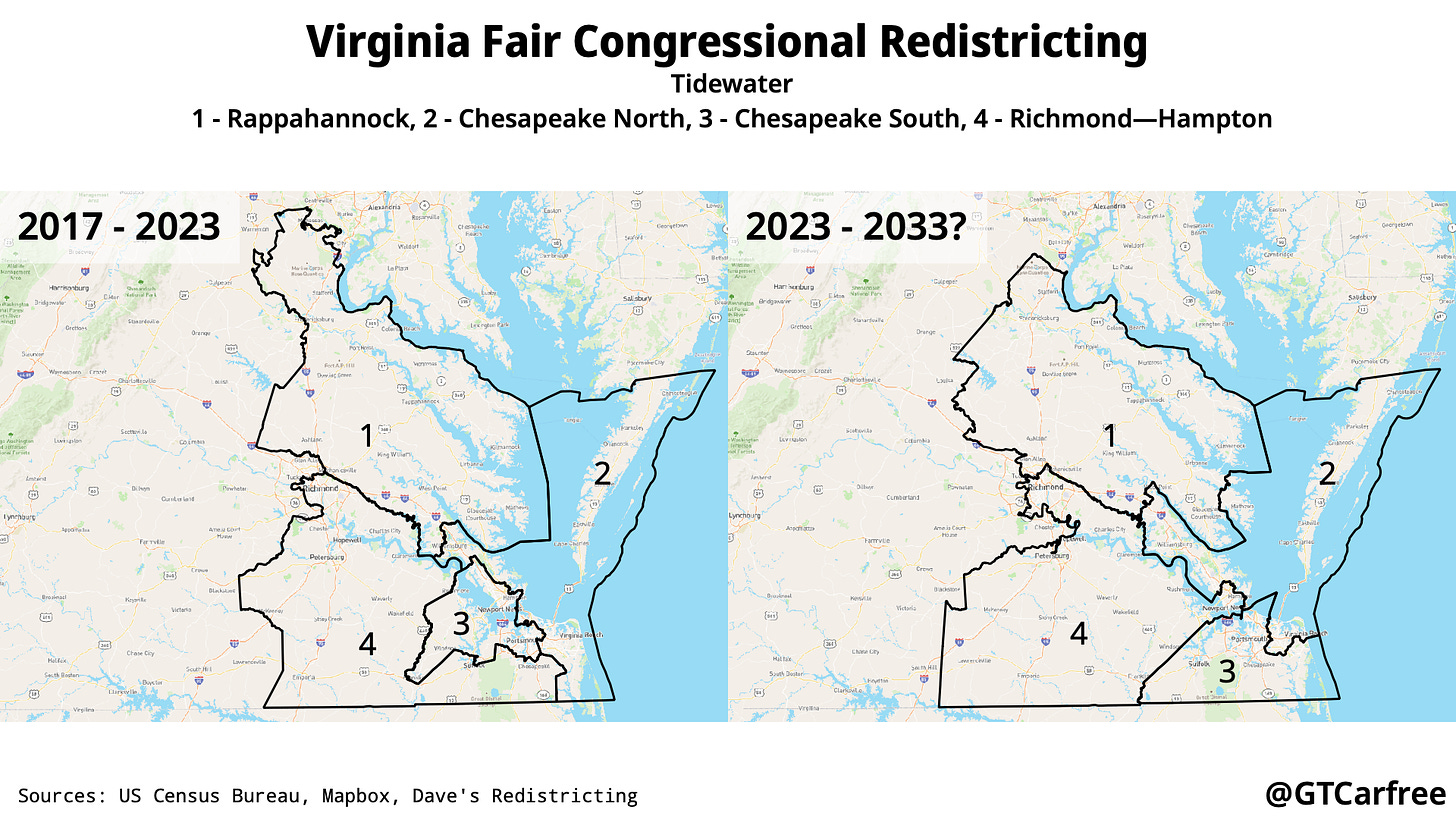

Dr. Grofman’s map adjusted boundaries in the eastern part of the state, creating two black-opportunity districts (3 and 4) in place of one. It was used for Congressional elections from November 2016 onwards. However, since the original complaint was narrow in scope, it left most boundaries in the western and northern part of the state unchanged.

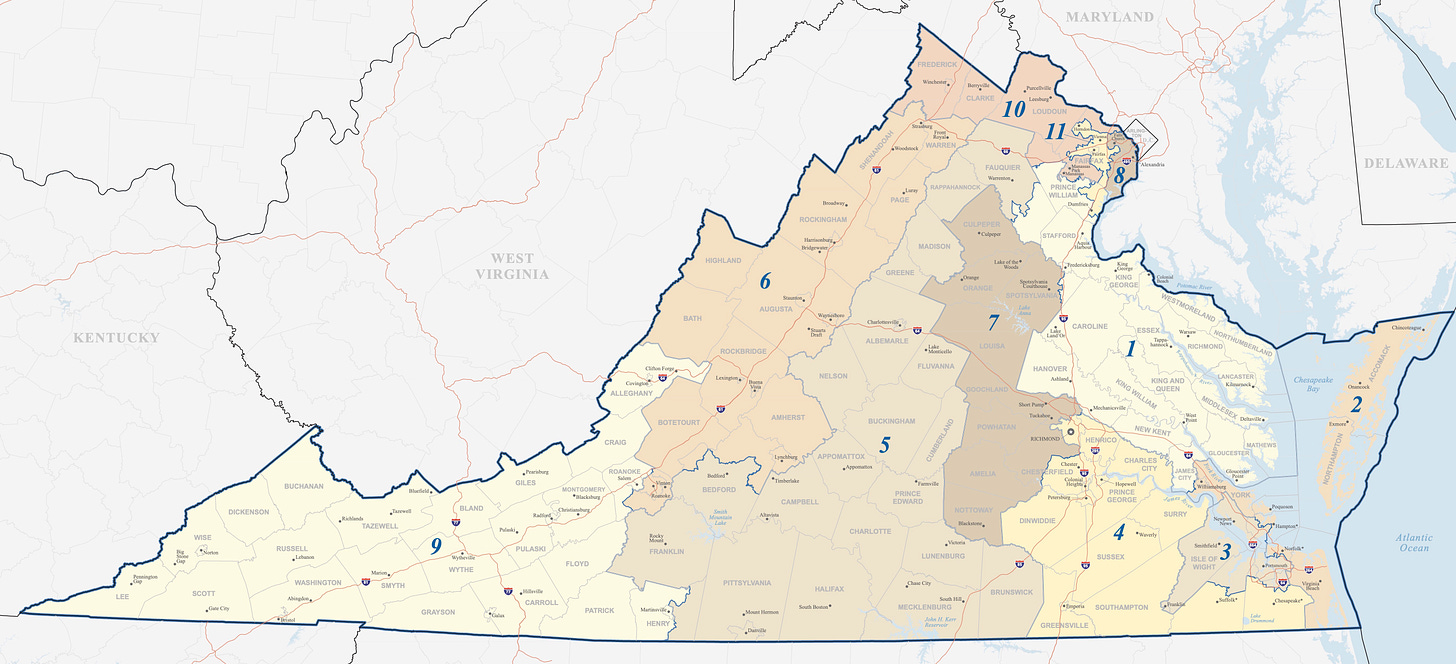

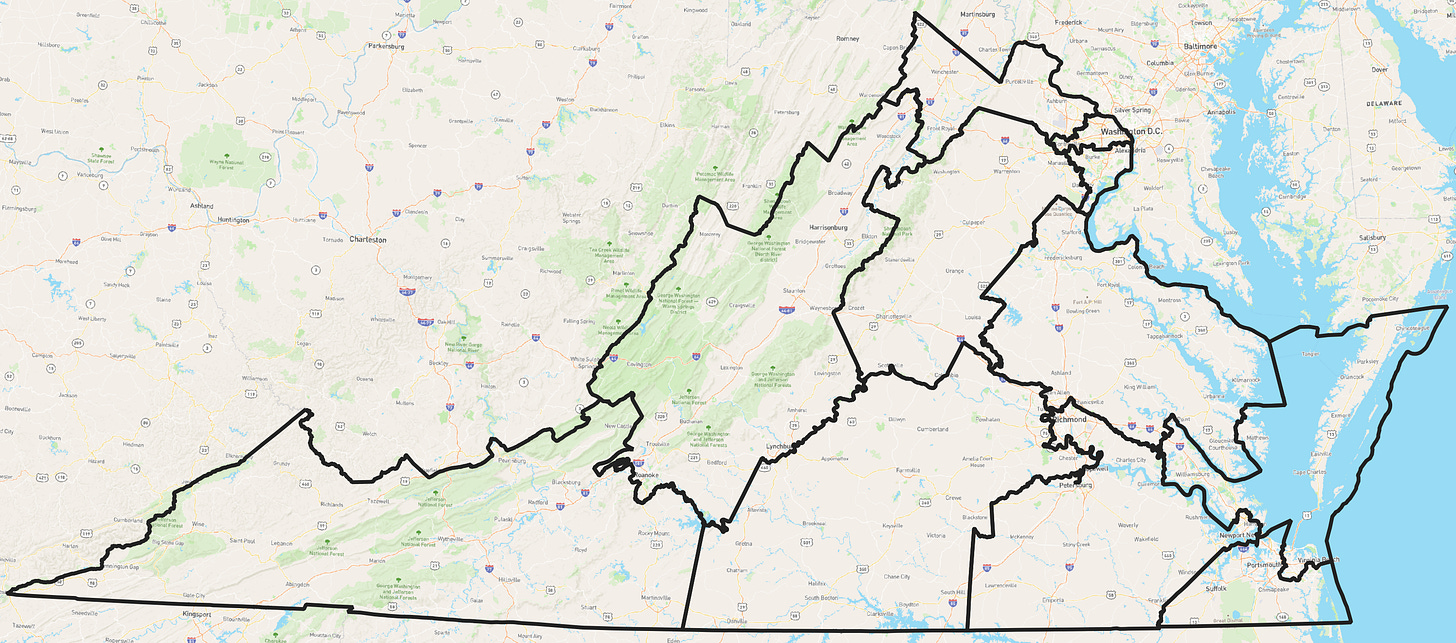

In 2020, Virginian voters endorsed a proposal to introduce a redistricting commission, composed of two members each from the minority and majority parties in the Virginia House of Delegates, two members each from the minority and majority parties in the Virginia Senate, and eight Virginian citizens. With a more structured and independent process, the map they draw will likely be less gerrymandered than past ones. My map respects the goals of the court-ordered mid-decade redistricting while altering other district boundaries to improve compactness and keep communities of interest together.

In the Tidewater region, the First District becomes more compact. The Fourth District is now a black-majority VAP district, and the remaining ones are adjusted accordingly to ensure population equality.

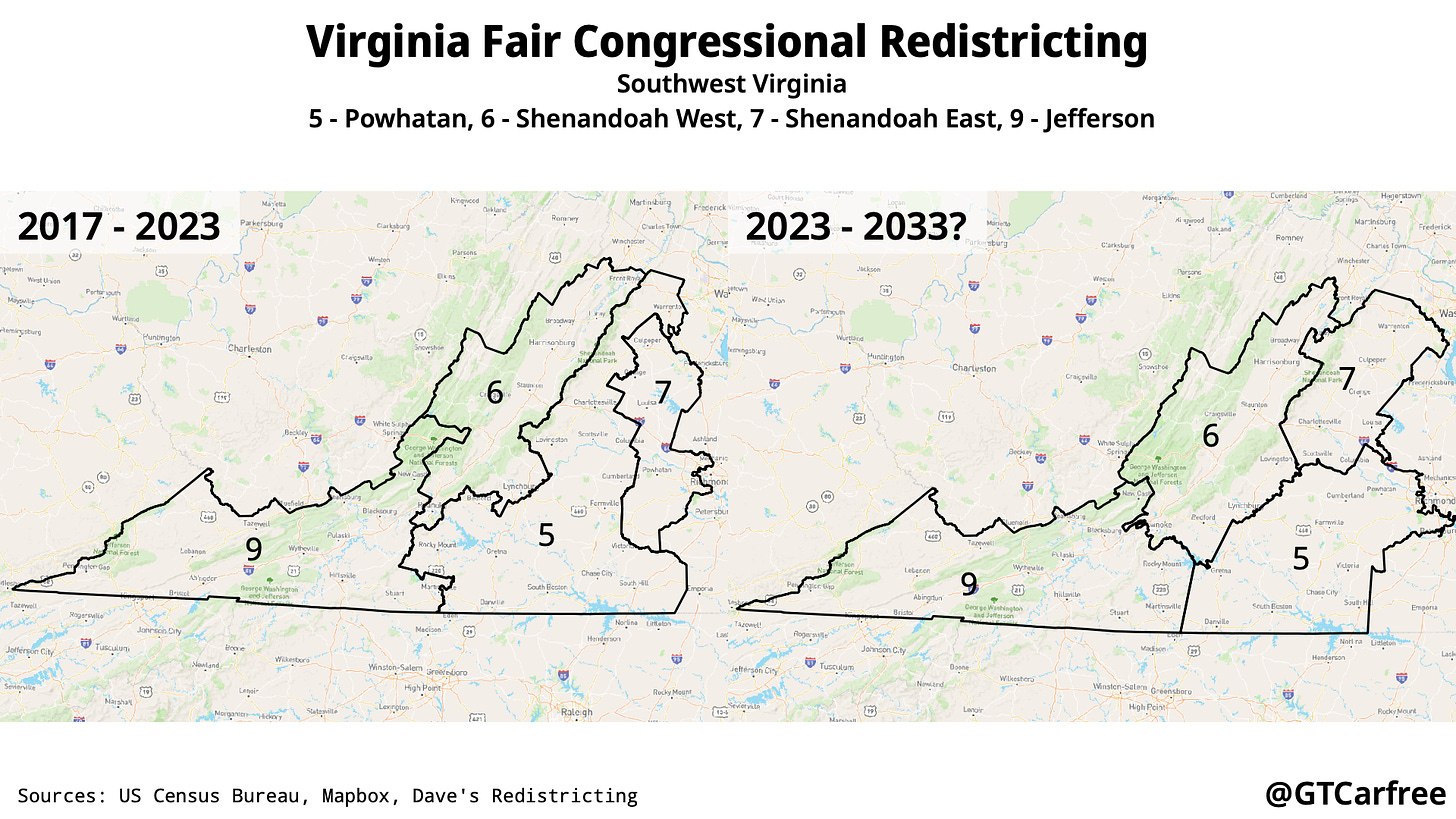

The boundaries of the Sixth and Ninth Districts received minor alterations to account for population changes while the other two districts received more significant changes. This was especially apparent with the Fifth District, which stretches in its current iteration contains rural areas in the southern part, urban and suburban areas near Charlottesville, and exurban areas near Washington. This proposal creates a more compact north-south split.

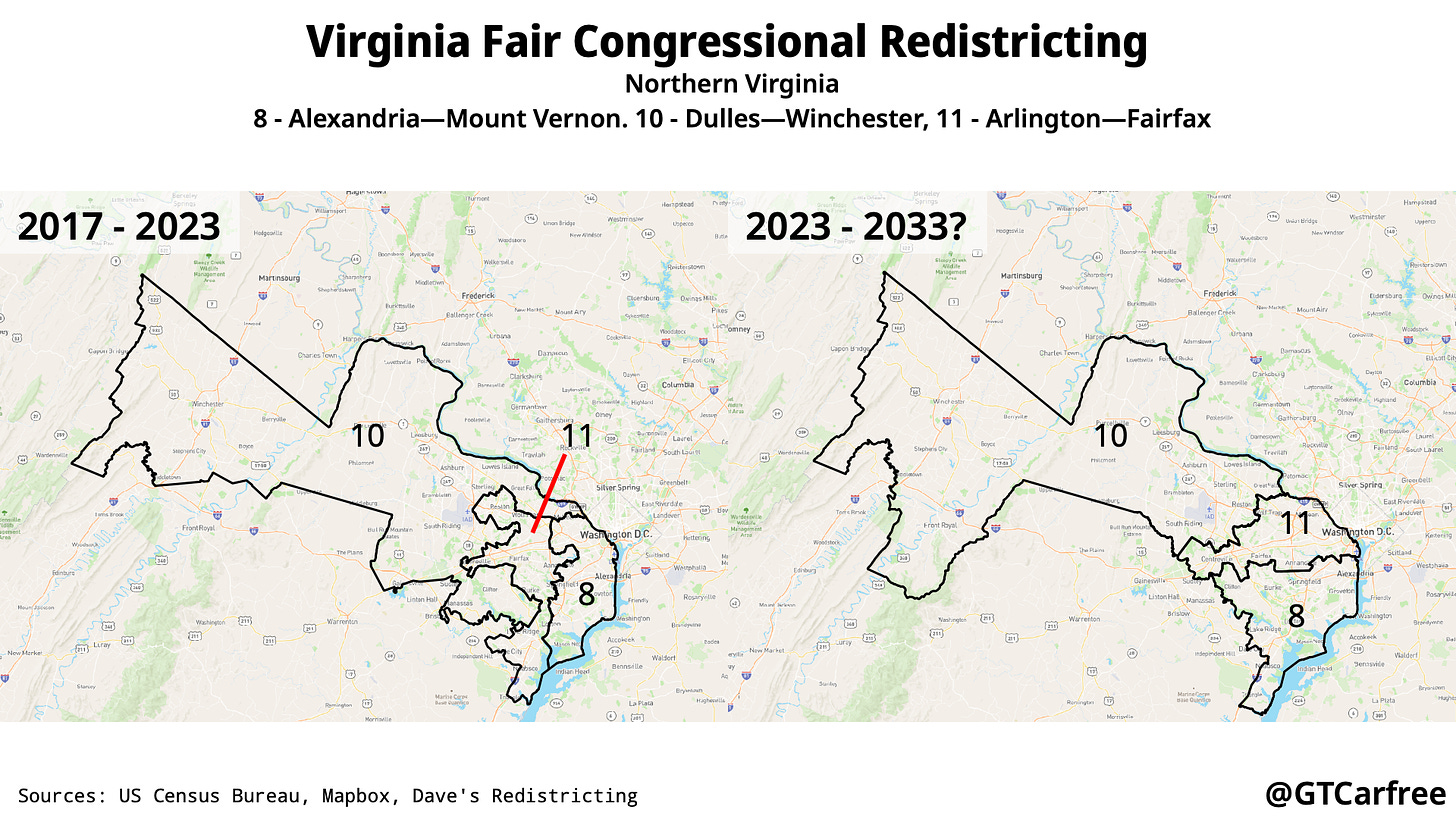

Northern Virginia is a part of the Washington metropolitan area. Boundary changes serve to make the districts more compact. The Eighth District now includes Alexandria and other municipalities to its south, while the Eleventh District is entirely within Fairfax and Arlington Counties. The Tenth District stretches to West Virginia and combines suburban and exurban areas along parts of the Potomac River, with most of its population in Loudoun County.